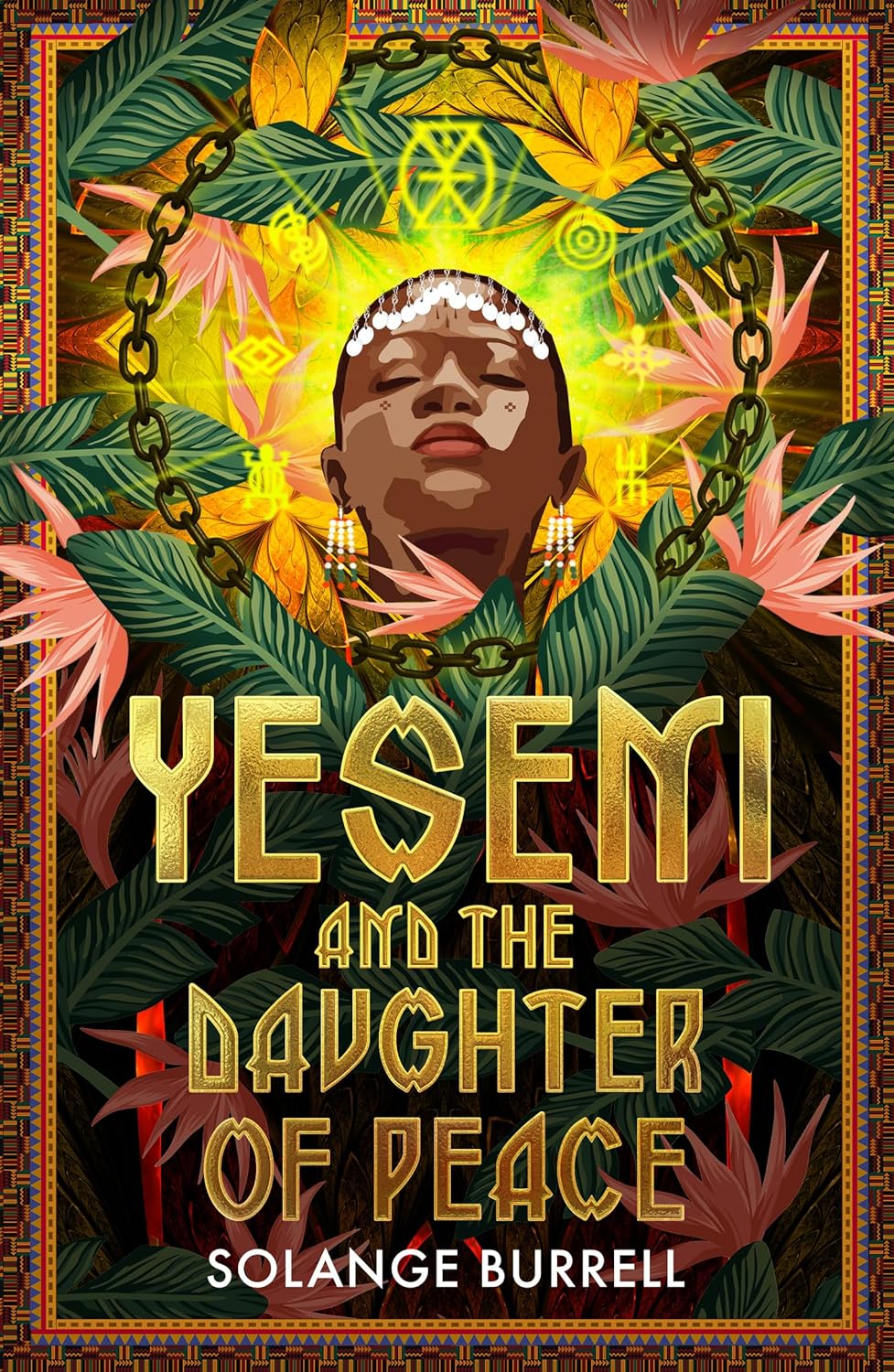

The year is 1748. Elewa, known as ‘the Daughter of Peace’, bears a heavy responsibility on her young shoulders: to maintain the fragile truce between the warring peoples of her West African kingdom.

But as she begins to understand her role in the peace negotiations, even greater pressures emerge. Elewa discovers that she has Yeseni, a powerful gift that allows her to see events from any point in time, and to travel into the past and future.

When she experiences horrific visions of life aboard a slave ship, she realises she has to face the ultimate crossroads. She could use her gift to intervene in the past and try to prevent the transatlantic slave trade ever taking place. But that means she, as the Daughter of Peace, would be leaving her village behind at a precarious moment in the reconciliation process.

Whichever path she chooses to take, the future of her people lies on her shoulders.

Yesini And The Daughter Of Peace by Solange Burrell was published by Unbound Firsts on 30 November 2023.

As part of this #RandomThingsTours Blog Tour, I am delighted to share an extract from the book with you today.

Extract from Yesini and the Daughter of Peace by Solange Burrell

From a very young age, the reasons for war were explained to me in depth, or as much detail as I could comprehend at the time. Papa said that I was implying questions with my tone as soon as I could make sounds. He said that I would point at things and raise the inflection in my voice, uttering obscure non-words, then await an explanation from them.

Papa would often joke with Mama that I even wanted to know why the breeze blew through the trees. He would do this when I asked the more difficult questions. The ones that did not really have an answer, or, at least, not one that could be articulated in a nice, neat package and finished with a bow. I think this is how Papa felt when I asked him why we had been at war with the Okena for so many years. We sat in our back yard on chairs Papa had hand-carved from an old tree stump and leftover logs from the debris of the last tropical hurricane. The sun was low in the sky, and it was nearly my bedtime, but Papa had promised me one last game of Choko before I went up. I used the game as a way to pry answers to the many questions I had, and I remember him smiling and shaking his head at me. I think I was around six or maybe seven years old at the time. After looking at me, he stood up, turned around to the faucet and loosened it to wash the blood off his hands.

‘Pass me the cloth, Elewa.’ He pointed over to the row of clean cloths that he used as makeshift bandages: they were hanging on the washing line. The rope used for the washing line was made of plant fibres that were delicately twined or braided to form the cord. Papa nailed each end of it to the exterior back wall of our house and whenever it was full of clothes, it made the house look all festive and spruced up, but the clothes would cover the back door, so we would have to crouch to get in and out until they dried.

Elewa was the nickname that Papa had given me; it literally meant ‘pretty’ in his native tongue. Papa always said I had a face that the world should see. Mama loved the name as well. “It means more than just pretty you know!” she’d say, but at that time I was content with ‘just pretty’.

I strolled over to the washing line, purposely dragging my feet along the red dirt to make a pattern in the ground before a gorgeous agama lizard with a bright orange head scurried through my feet.

‘Hey!’ I yelled.

‘If you want to play one last game before bedtime, you will have to hurry up!’

I jumped up underneath the washing line and grabbed a clean cloth for him.

‘Now hold there and do not let go,’ he said. It was the first layer of the bandage to be wrapped around his wounded hand; he needed me to hold it firmly, so that it would stay in place. I felt so important and proud that I could assist my papa in this way. The wound was quite deep and just off the centre of his palm. As Papa wrapped the cloth around his hand, my finger, which was holding the first layer of cloth started to feel trapped.

‘So, your question was, why do we go to war?’ he asked.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment