An inspiring guide to focusing on what matters most in life--and hitting delete on what doesn't.

Life is noisier, messier, and more complicated than ever. In our quest to keep up, we can lose sight of what we care about most, and instead try to do it all--with mixed results.

In this beautiful call to examine and edit our lives, writer Elisabeth Sharp McKetta shares nine simple ways to cut through the clutter, drama, and overwhelm of modern life to live with more intention and joy. Inspired by her own experiments with reprioritizing, tiny house living, and finding the right balance of work and family time, Edit Your Life brings together personal narrative and practical takeaway, with inspiring results.

Whether you're pivoting, downsizing, relocating, or just ready to have more time and energy for the people and activities you love most, this engaging and practical guide will bring you on a journey of exploration and reflection--and point you toward the life you truly want to live.

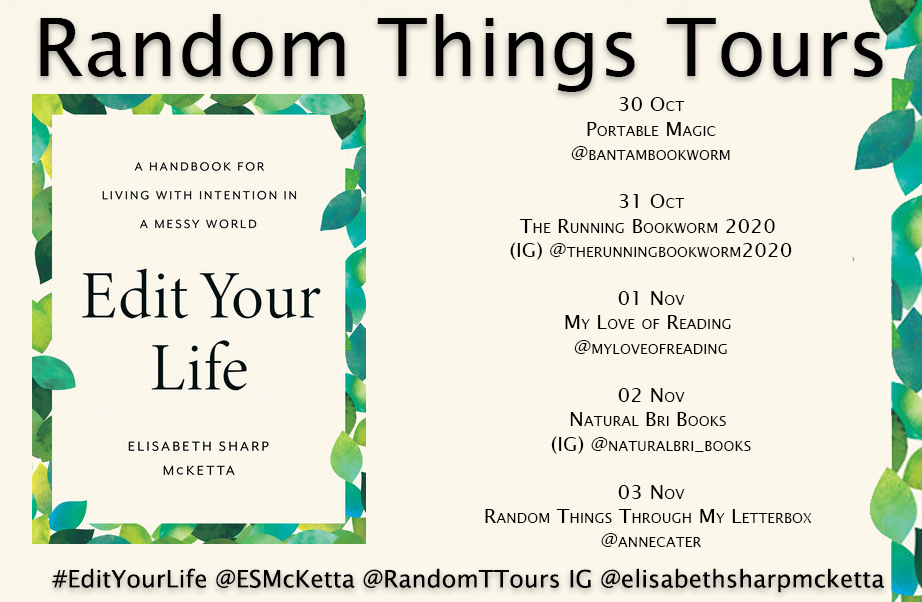

As part of this #RandomThingsTours Blog Tour, I am delighted to share an extract from the book with you here today.

Extract from Edit Your Life by Elisabeth Sharp McKetta

ASK: WHAT IS IT?

Looking Closely

Looking closely is an editor’s best tool. To revise a thing, whether a poem or a life, means literally to look again. It is a way of creating enough distance to see clearly. Often I see a writer frustrated with a project and wanting it to be something that it’s not, and the best gift a good editor can give is to point gently to what it seems to want to be. Only then we can find its true form.

This, then, is our work with our lives. To look at the facts as neutrally as possible, without judgment; to look again; to see the direction in which our life desires to grow; and to prune along its natural shape. To ask questions whose answers will give us good information, such as: What does it contain? What boundaries confine it? What does it feel like to live it? What are its energy sources?

When I put this idea forth—first, just look—to my writing students, I can see their doubts. I understand why. Labour is built into the human species. It is no surprise, then, that often we feel that if we are not solving a problem or offering critique or doing active work, we’re not doing anything. Yet we are bound to edit badly unless we first take time to understand what this thing is that we have on our hands—before worrying about what it should be or imposing our will upon it.

Before considering any edit, I ask these three questions in order:

1. What is this trying to be or do? (What is its ideal version?)

2. What works? (How does it succeed in meeting that ideal version?)

3. What is needed? (Where are the gaps between its “now version” and its ideal version?)

Asking these questions—a formula for looking closely—is so simple, and so applicable to any situation.

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment